VR is the best medium to tell story of infertility

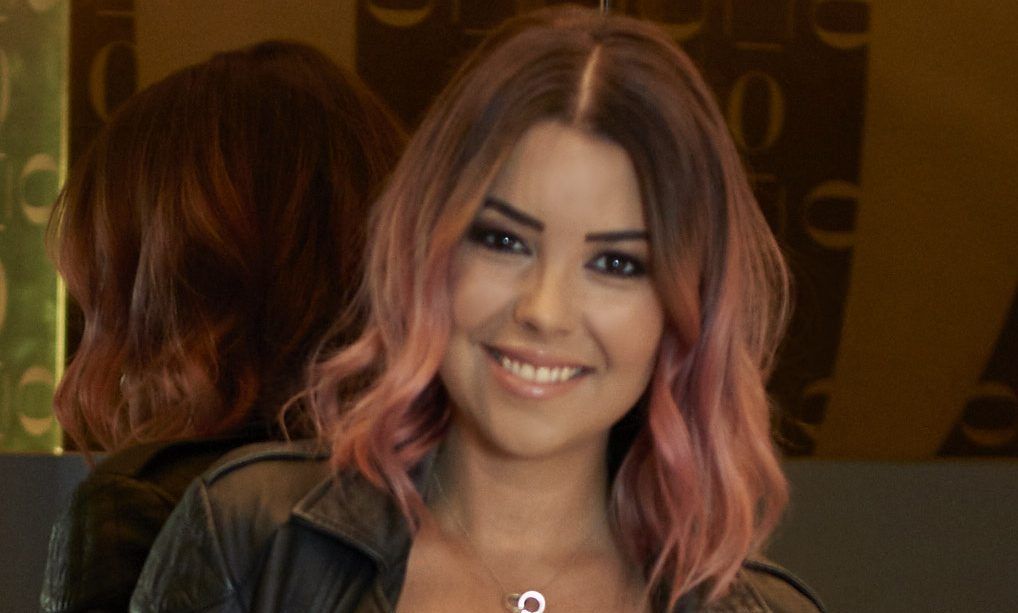

Dee Harvey is the writer and director on a new documentary being told in VR format. The VR film explores the issue […]

June 5, 2018

Dee Harvey is the writer and director on a new documentary being told in VR format. The VR film explores the issue of infertility; called Hope is the New Killer.

“The film will bear witness to a very common experience that’s talked about very little,” says Dee. “At least one in seven couples encounter fertility issues.”

She explains how the documentary is taking shape. “We’ll use the verbatim technique. People who have been affected by infertility will share their stories in an intimate format.”

Using VR to produce this type of documentary is not just about applying a 2D film onto a 3D headset.

“We need to use VR for the things it does well, to tell a story in a provocative way. No one has done it exactly like this,” she says.

How can a filmmaker get a VR piece commissioned?

“There are various pockets of money about,” says Dee.

As an example, she points to how Digital Catapult and Innovate UK partnered to fund 10 projects in VR at £20,000 each. “Also NI Screen has added VR short films to their funding list,” she adds.

When I suggest that the path is perhaps less trodden than with normal TV or film, Dee replies, “Oh absolutely. There’s a whole industry and infrastructure that already exists for cinema and TV. These routes to market are only just being explored in VR. But people from both film and gaming industries are coming together, which is exciting.”

How will VR transform the arts?

“VR is not going to damage or kill any other industries,” Dee says. “It’s a bit like theatre in how the story is told. It’s also a lot like games in how it’s interactive. But it’s a new art form offering so many exciting possibilities.”

How will people access your film?

“We don’t have partnerships in place yet with a distributor – this is all being figured out. VR cinemas are definitely a new thing – which is very important because, even as VR is so personal, people want to consume VR with others.”

Dee explains that the way VR is consumed by its audience is so different to other art forms.

“Your vision is occluded when you wear a VR viewer and you’re right in the middle of the story. The reaction can be very visceral. People want to talk about what they just saw, after they experience VR. It can be disappointing to not have human interaction straight after.”

This is why Dee feels that “people will be willing to pay a ticket price to attend a VR cinema, where everyone is sitting together consuming the same VR through their own personal headset.”

Are there any VR cinemas in Ireland yet?

“Not that I’m aware – there are examples in England,” she says.

In this excellent podcast recently recorded by Davy Sims, Dee discussed how VR needs to be experienced in a “safe space.”

Dee says, “You need to feel secure. For example if a woman is carrying a handbag, when you hand her a headset to wear, someone else needs to be there to look after the bag. If someone’s job is to hand out headsets, It’s not just a body handing out headsets, that person also needs to make people feel they’re in a safe space.”

She continues, “Good VR experiences have thought these issues through.”

How is it different to see a film in VR than 2D?

“The experience can be more shocking. There are some quite exploitative VR documentaries – for example, filming in refugee camps and you’re right up in the faces of children – some of it can be uncomfortable.”

For readers who may not have a VR headset, you can still get a sense for what a VR documentary is like with the BBC’s Rome Invisible City.

What’s your production schedule?

Dee says, “We’re still in development, and aiming to release a prototype or a short in the Autumn.”